After a suitably long delay, here comes a look at the fighter-bomber F-105 Thunderchief, known as the “Thud” by its air-crew. Much like the B-58 Hustler, the F-105 fell into a gap between its original intended design and what it ended up being used for. Unlike the B-58, the F-105 saw extensive use in the bombing campaigns in South and North Vietnam during the Vietnam War, and suffered a staggering 47% loss rate (Of 833 built, 334 were lost to enemy action, and 61 to accidents), resulting it it being pulled from service towards the end of the conflict.

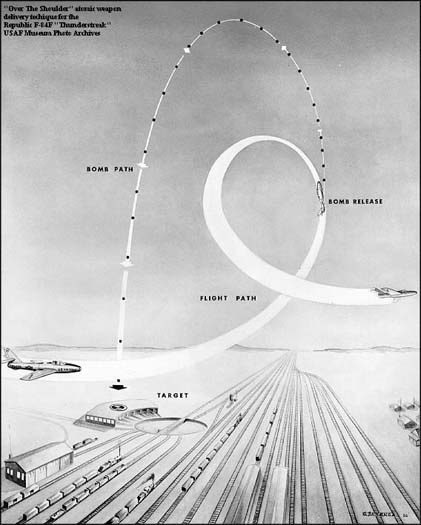

Originally, the F-105 was designed with the European Theater of Operations in mind: A huge supersonic low altitude fighter-bomber capable of carrying a tactical nuclear weapon into the beating heart of a hypothetical Soviet advance into the Fulda Gap. Theoretically the speed of the F-105 was supposed to allow it to survive entering contested airspace, deliver its payload, and return to base (as long as said base wasn’t overrun by Soviet troops or nuked into radioactive dust), but reality would likely have made it a one way trip due in part to its delivery system: the “idiot loop.”

I’m sure that you, as you’re reading this, have often wondered how aircraft can survive deploying a nuclear weapon, and there are two options. The first is to fly high enough that the time between your plane dropping the nuke and it detonating can give you enough time to get out of immediate danger, and *hopefully* not cook your eyeballs in the bargain. However, flying high meant you were exposed to both enemy air-defenses AND high flying interceptors, so the likelihood of you getting to the target area in once piece remains low. The trials and tribulations of the B-58 demonstrates the challenges faced by these kinds of designs.

The other remaining approach is to go in low and fast, hoping that you can use the terrain to mask your approach from enemy fighters, and zip past the targeting envelopes of air-defenses fast enough that they cannot track you effectively. Now, if you are moving low, and fast, surely there must be some way of ensuring that a nuclear weapon both detonates on target AND make sure that (in theory) the pilot isn’t immediately killed by the explosion. The solution, my friends, is “toss bombing,” otherwise known as the “idiot loop.”

It sounds simple, in theory. Toss the bomb high enough that you don’t have to slow down your plane enough to get targeted by local air-defenses, while lofting it to buy you time to make your getaway in one piece. However, the delivery of a tactical nuke to a high value target is tricky under ideal circumstances, let alone one where you’re executing a high-G maneuver to fling a bomb over your shoulder like a bride throwing a bouquet. Thankfully, we haven’t needed to see this execution in action.

With American intervention in Vietnam, the F-105 found itself filling a slot it was never intended to fill, going from nuclear interdiction in Central Europe to conventional bombing in a highly unconventional war. Using low-altitude dive bombing placed F-105 pilots in the sights of increasingly elaborate Vietnamese air-defenses for an extended time, and at the same time Vietnamese MiG fighters could easily outmaneuver (but not outrun!) the F-105 and their escorts. Combined with exacting and at times ridiculous rules of engagement in North Vietnam, F-105 pilots often felt they were fighting both the North Vietnamese and policymakers in DC as their sorties took them from downtown Hanoi one day, and bombing paths in the jungle to the next with little rhyme or reason.

In sum, F-105 pilots found themselves engaged in dangerous missions that were barely in the performance envelope for their aircraft. From nuclear interdiction to bombing car parks on the Ho Chi Minh Trail, the F-105 served gallantly as a bomb-truck, but ultimately earns the dubious honor of being the only American aircraft phased out due to combat losses.